Why a series of posts on the human ear canal? The answer is straightforward. The human ear canal is an important structure for those who work with the hearing impaired, but also for many other specialists. It is a pathway that many frequent in identifying and resolving issues related to hearing, whether they are disability or recreational related.

“Passing through the ear canal” could be analogous to getting in and driving a car, where few take the time to inquire about and understand the mechanisms involved. However, an improved knowledge of the ear canal – its anatomy and physiology – will assist the practitioner/researcher/consumer in understanding why things happen in the ear canal, and better prepare them for problem resolution and/or acceptance.

Professionals who fit hearing aids must have a good understanding of the external auditory meatus (ear canal). This information is important for proper evaluation of the hearing mechanism, for taking ear impressions, and lastly, and perhaps that which has the greatest long-term impact, relates to how an earpiece (hearing aid or other) directs or prevents sound from impinging on the tympanic membrane (ear drum). Does the coupling device render this communication properly and comfortably?

the temporal bone." width="162" height="163" />

the temporal bone." width="162" height="163" />

Figure 1. Bones of the skull. The ear canal is housed in the temporal bone.

Many factors must be considered when discussing this topic, and this next series of posts will take in in-depth look at the human ear canal. In doing so, the series is intended to provide information to help in understanding and resolving problems related to earpieces designed for the ear, regardless of the listening device. The intent is to focus on the anatomical and physiological issues, and not on hearing measurement or pathological issues. These would be better managed specifically.

The ear canal is housed in the temporal bone (Figure 1).

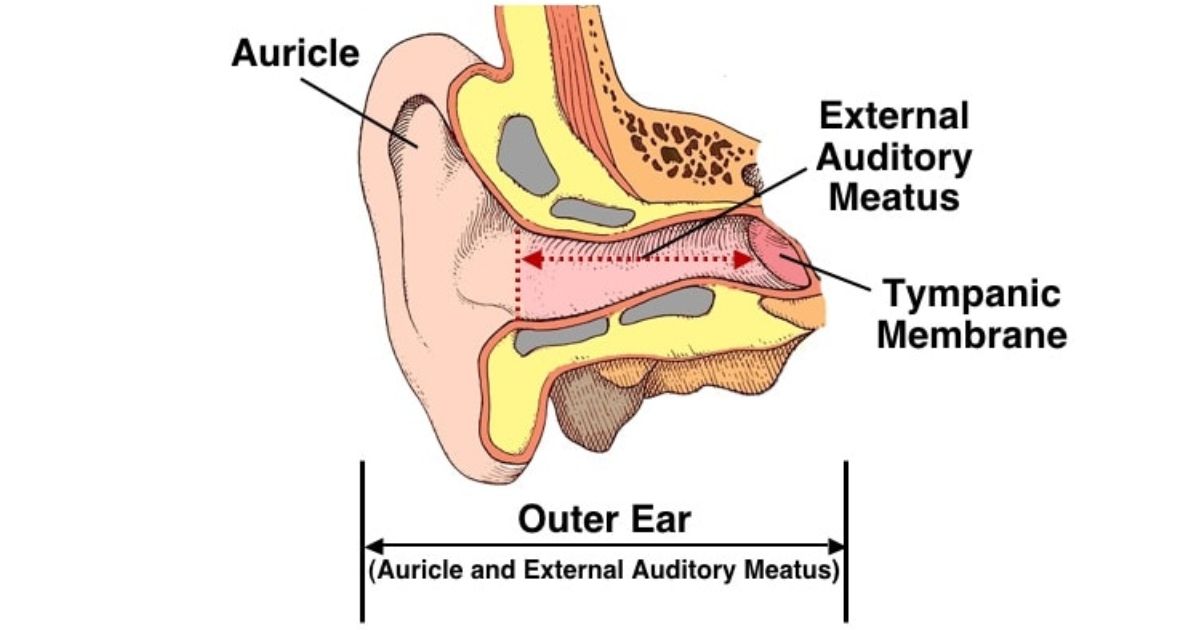

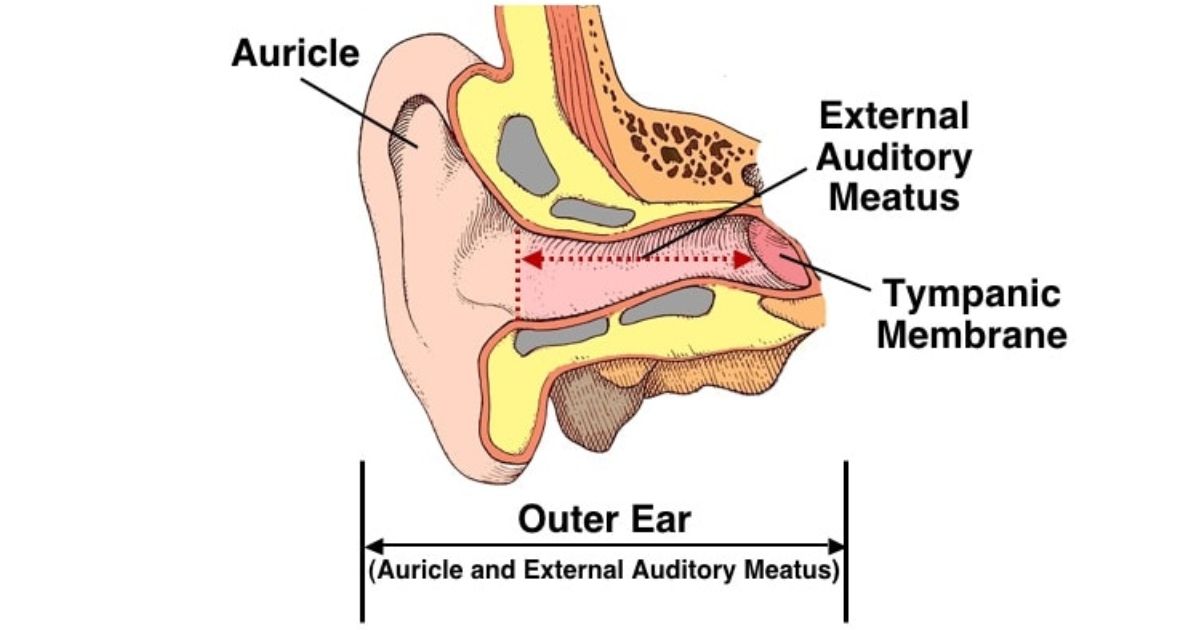

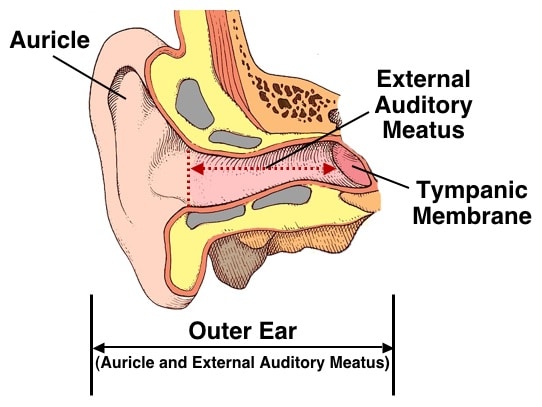

The outer ear (Figure 2) consists of the auricle (pinna) and the external auditory meatus (ear canal). It ends at the tympanic membrane (ear drum). The ear canal itself is shorter than this, and is essentially a skin-lined cul-de-sac that extends from the aperture (opening) of the ear canal to the tympanic membrane (eardrum).

Figure 2. Outer ear, consisting of the auricle and the external auditory meatus (canal). The external auditory meatus extends from the aperture (opening) of the ear canal to the tympanic membrane (shown by the dotted line).

The primary function of the ear canal is to serve as a conduit for the passage of sounds to the tympanic membrane (TM). It serves also to protect the middle and inner ears from external trauma by impeding (using distance, shape, and chemical composition) the entry of foreign objects, and by mediating fluctuations in environmental temperatures.

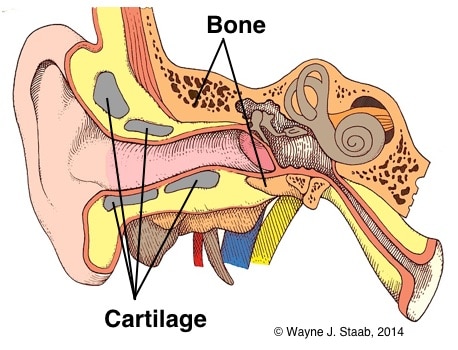

Figure 3. The skeletal structure of the external auditory meatus consists of cartilage distally, and bone medially.

The skeletal structure of the ear canal (external auditory meatus) consists of elastic cartilage laterally (cartilaginous portion) and bone medially (osseous, or bony portion). This is essentially the same for all individuals, although considerable variation in size, shape, and orientation occurs (Figure 3).

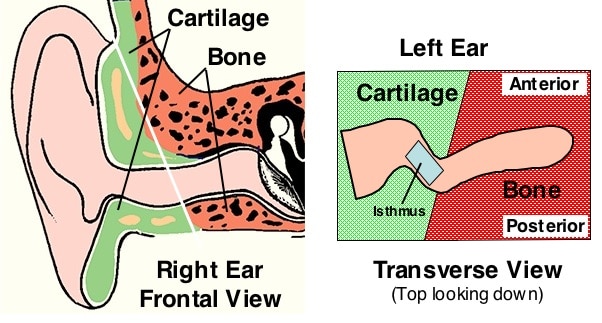

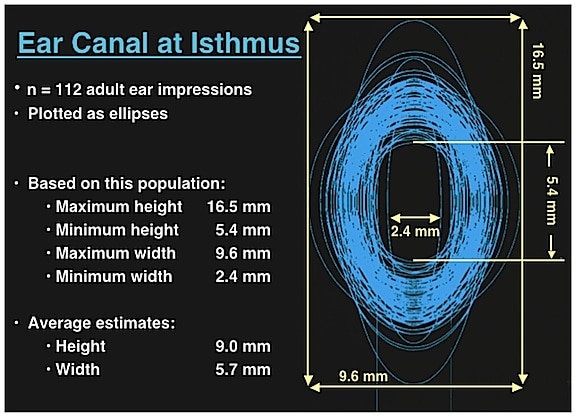

The narrowest part of the ear canal (isthmus) is located near the junction of the cartilaginous and bony canals (Figure 4). The cartilage of the ear canal is continuous with that of the auricle (pinna). Medially, the cartilage is firmly attached to the bony canal. Figure 6 provides measurements of the range of vertical and horizontal dimensions of the isthmus.

Figure 4. Cartilaginous versus osseous (bony) sections of the external auditory meatus

The cartilaginous part of the ear canal constitutes approximately the outer one-third (mostly) to almost one-half of the total length, but this varies among individuals.

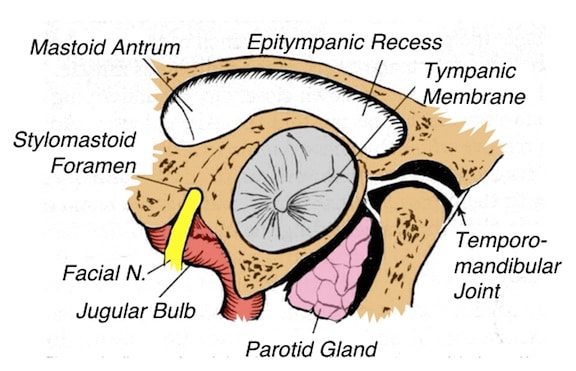

Figure 5. Adjoining structures/areas to the external auditory meatus (right ear), as viewed from the aperture of the ear canal toward the tympanic membrane.

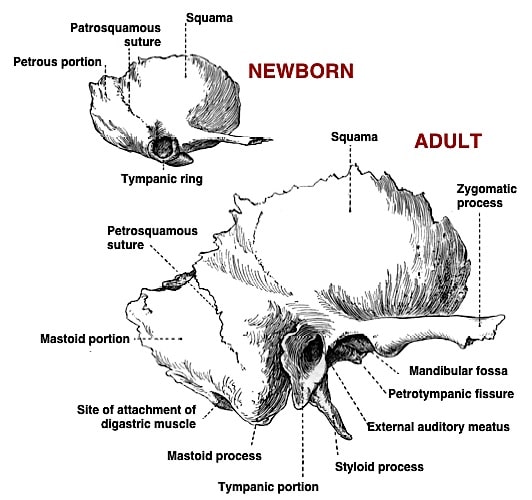

The medial one-third to one-half of the ear canal is osseous (bone) and is oriented in a forward and downward direction. The downward (and inward) orientation is displayed in Figure 4 on the left image, and identified by the white line. The right image of Figure 4 shows that the posterior (and superior, as shown in the left image) portion of the ear canal has greater osseous lining. The ear canal is slightly concave posteriorly so that the ear canal as a whole is slightly S-shaped when viewed from the top (Figure 4, right image). However, there is considerable variation in the configuration and size. Posterosuperiorly, the bony meatus is related from within out to structures of the mastoid bone. Inferiorly, the meatus is in close relation to the jugular bulb, as well as close (posteroinferior) to the facial nerve (Figure 5).

Figure 6. Range of vertical and horizontal measurements of the isthmus taken from 112 impressions made on live subjects. (Staab & Sjursen, 2000).

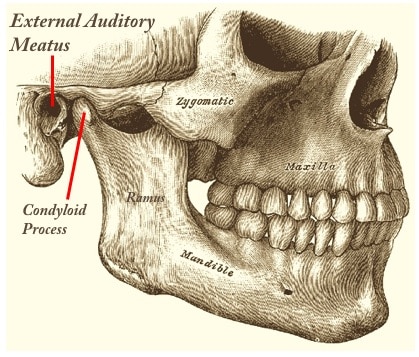

The middle third of the ear canal is graduated between bone and cartilage, with bone having greater impact along the posterior wall of the canal (Figures 4 and 7). The bony meatus is related anteriorly and inferiorly to the parotid (salivary) gland and to the temporomandibular joint (Figure 5). Condyloid movements of the ramus of the mandible, as in speech or mastication, can be transmitted to the cartilaginous portion because of the proximity of the mandible to the ear canal (Figure 8).

Figure 7. Temporal bones of newborn and adult, showing differences, with special emphasis on the bony walls of the ear canal opening. In the newborn, the tympanic ring is short and incomplete. However, in the adult, the posterior-superior portion of the ear canal develops greater bony lining than does the anterior-inferior portion of the ear canal.

the ramus of the mandible articulates just anterior to the external auditory meatus, resulting in dimensional changes in the ear canal during jaw movement, regardless of the purpose (speaking, mastication, etc)." width="226" height="193" />

the ramus of the mandible articulates just anterior to the external auditory meatus, resulting in dimensional changes in the ear canal during jaw movement, regardless of the purpose (speaking, mastication, etc)." width="226" height="193" />

Figure 8. The condyloid process of the ramus of the mandible articulates just anterior to the external auditory meatus, resulting in dimensional changes in the ear canal during jaw movement, regardless of the purpose (speaking, mastication, etc).

References:

Wayne Staab, PhD, is an internationally recognized authority in hearing aids. As President of Dr. Wayne J. Staab and Associates, he is engaged in consulting, research, development, manufacturing, education, and marketing projects related to hearing. His professional career has included University teaching, hearing clinic work, hearing aid company management and sales, and extensive work with engineering in developing and bringing new technology and products to the discipline of hearing. This varied background allows him to couple manufacturing and business with the science of acoustics to bring innovative developments and insights to our discipline. Dr. Staab has authored numerous books, chapters, and articles related to hearing aids and their fitting, and is an internationally-requested presenter. He is a past President and past Executive Director of the American Auditory Society and a retired Fellow of the International Collegium of Rehabilitative Audiology.

**this piece has been updated for clarity. It originally published on June 9, 2014